Known around the world as the “King of Cheese,” Parmigiano Reggiano isn’t just a cheese people grate over pasta, to Italians, it’s part of their identity. To witness the art behind it, I visited a dairy in Parma, Italy, where it’s still made the way it has been for hundreds of years: by hand, with nothing but milk, rennet, salt and time.

After spending half the day watching Parmigiano Reggiano being made, I can say I have a deeper respect for the cheese and the process.

The day began early morning, I stood in a warm dairy as cheesemakers coaxed milk. Parmigiano Reggiano is only made once a day from two milkings: 50% of yesterday’s low-fat milk and 50% of today’s full-fat milk. The milk mixture is gently heated in copper vats, which carry 1,200 litres. Each vat produces two wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano. It’s satisfying to watch the colour of the milk change from bright white to creamy custard, and then from a liquid to a solid.

The day began early morning, I stood in a warm dairy as cheesemakers coaxed milk. Parmigiano Reggiano is only made once a day from two milkings: 50% of yesterday’s low-fat milk and 50% of today’s full-fat milk. The milk mixture is gently heated in copper vats, which carry 1,200 litres. Each vat produces two wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano. It’s satisfying to watch the colour of the milk change from bright white to creamy custard, and then from a liquid to a solid.

The cheesemakers then test the curd’s consistency by gently swirling their hands in the mixture. Once it’s firm enough, they break it into small granules using a large whisk called a spino. The cheesemasters know exactly when to increase the speed of the stirring in order for the curds to settle, based on feel, not taste. The cheese tells you when it’s ready, not the other way around.

The making of the cheese is a 20-minute process, followed by 45 minutes of steaming. At this time, the curds sink to the bottom of the vat, as they dry up and firm up. Two cheesemasters wrap the heavy mass in cloth, as they separate it into two; at the same time, they’re also moulding and reshaping it. From there, the wheels are pressed and rotated for several days.

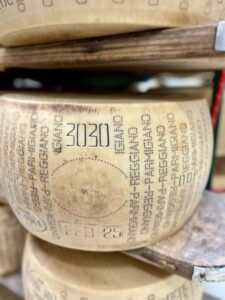

While the cheese is still soft, the plastic belt embossed with the words Parmigiano Reggiano is wrapped around it. It’s a unique identification number, similar to a birth certificate, marking its origin and guaranteeing its authenticity.

After that, the cheese goes into a salt bath for about 20 days, where it slowly absorbs salt and begins to form its signature rind. Then the wheels go into a sauna to dry for a few more days. From there, the wheels are moved into the aging room.

Walking into the aging room feels like stepping into a cathedral of Parmigiano Reggiano. The air is slightly humid with the savoury, earthy smell of aging cheese. Rows upon rows of wheels stretch from floor to ceiling, neatly stacked on wooden shelves.

Fun fact #1: Parmigiano Reggiano is naturally lower in fat than most cheeses because the cream is skimmed off the milk before production. That removed fat is then used to make butter, Grana Padano, ricotta and other dairy products. Nothing goes to waste. Even the leftover whey is fed to the pigs used for Prosciutto di Parma, creating an efficient, deeply interconnected food system.

Fun fact #2: Parmigiano Reggiano is considered naturally lactose-free because the starter cultures eat all the lactose during the first hours of cheesemaking. And then 12+ months of aging eliminates any remaining trace.

Each wheel weighs around 40 kilograms and rests for 12 months, up to 36 or more. When the cheese reaches one year, an inspector from the Consorzio Parmigiano Reggiano examines it to ensure the texture and internal structure meet the required standards for certification. The wheel is tapped with a small hammer to detect any defects. This process maintains PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) standards, guaranteeing that the buyer is getting true Parmigiano Reggiano and that every wheel is aged consistently and is of the highest quality.

There are only five provinces in Italy where Parmigiano Reggiano can legally be produced, a testament to the care and tradition behind every wheel.

After seeing how it all gets made, we sat down to taste the cheese at three different ages: 12, 24 and 36 months. At 12 months, it was soft, with a mild sweetness. The 24-month-old had that familiar crumbly texture with a rich, nutty flavour that lingers. By 36 months, it was sharp, complex and deeply savoury. Each stage revealed not just the evolving flavours, but more so the extraordinary patience and craft required to make it.

Add a comment